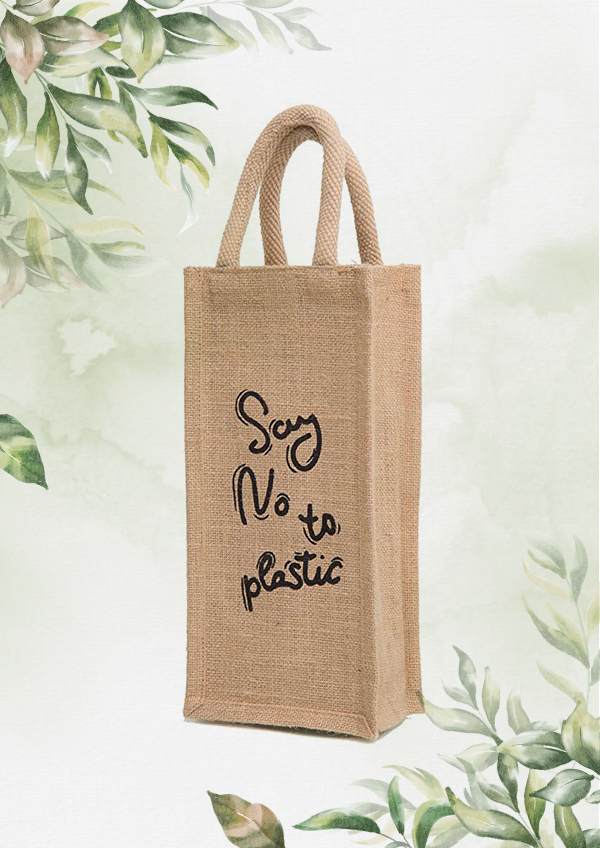

Jute Bags Manufacturer In India

Choose From Our Vast Ranges Of Jute Bags

Our Collection Of Export Quality Jute Bags

Know more about Jute here…

In an era where sustainability has become more than just a buzzword, jute stands tall as one of the most promising eco-friendly materials available today. Known as the “Golden Fiber”, jute has been used for centuries in textiles, packaging, and home décor. Growing environmental concerns, plastic bans, and a renewed focus on biodegradable materials drive its resurgence in the modern world.

This white paper explores the multifaceted potential of jute, from its natural origins and manufacturing process to its environmental benefits and role in the global economy. It also examines how jute bags have emerged as a practical, sustainable alternative to plastic, reshaping consumer habits and business practices worldwide.

With major global markets pushing toward green packaging and eco-conscious living, the jute industry is entering a renaissance phase. From fashion houses to supermarkets, jute is becoming a material of choice for those who value durability, affordability, and environmental responsibility.

Scientifically, jute comes from the stem or bast of two main plant species — Corchorus olitorius and Corchorus capsularis. Both belong to the Malvaceae family (the same family as hibiscus and cotton). These plants are tall, slender, and thrive in tropical and subtropical climates characterized by abundant rainfall and high humidity.

-

Corchorus olitorius, also known as Tossa jute, produces finer, stronger, and silkier fibers.

-

Corchorus capsularis, or White jute, yields coarser, cream-colored fibers that are traditionally used for sacking and packaging materials.

While both species look similar, Tossa jute grows slightly taller (up to 3–4 meters), has dark green leaves, and produces superior fiber quality, making it the preferred variety for modern textile and fashion industries.

Origins and Historical Significance

Jute’s history dates back thousands of years. Archaeological evidence suggests its use in the Indian subcontinent as early as the 3rd millennium BCE. Ancient Bengali farmers cultivated jute for making ropes, cords, and coarse fabrics used in household and agricultural activities.

During the British colonial period in the 19th century, jute gained global prominence. The first jute mill was established in Rishra, near Kolkata (Calcutta), in 1855. From there, Bengal became the global center of jute trade and manufacturing, exporting millions of gunny sacks and ropes worldwide. By the early 1900s, jute was second only to cotton in terms of global textile consumption.

For decades, jute powered the industrial growth of colonial India and later became a backbone of the economies of India and Bangladesh. It employed millions, shaping social and economic landscapes across eastern South Asia.

Physical Appearance and Characteristics

At first glance, jute fibers appear golden or off-white, smooth, and slightly glossy. Each fiber strand is long and flexible, allowing it to be spun into strong yarns and woven into a variety of textures.

Some of jute’s most notable physical characteristics include:

-

Length and Strength: Jute fibers range from 1 to 4 meters long and have excellent tensile strength, making them ideal for ropes, bags, and carpets.

-

Luster: The natural sheen gives it an appealing, silky look, hence the name Golden Fiber.

-

Texture: Slightly coarse but soft enough to be blended with other natural fibers.

-

Water Absorption: It has high moisture regain, meaning it can absorb water easily — useful for packaging but less ideal for long exposure to damp environments.

-

Biodegradability: Being plant-based, jute decomposes completely without leaving microplastic residue, enriching soil rather than polluting it.

Composition and Scientific Properties

From a chemical standpoint, jute is composed mainly of cellulose (60–70%), hemicellulose (13–20%), and lignin (10–12%).

-

Cellulose gives jute its structure and flexibility.

-

Lignin adds stiffness and durability, helping the plant stand upright.

-

Hemicellulose and pectin bind the fibers together, forming the bast within the stem.

This natural composition makes jute strong yet biodegradable, a rare balance in the textile world. Unlike synthetic fibers, which are derived from petroleum and persist in landfills for hundreds of years, jute returns to nature within months of disposal.

How Jute Grows: Climate and Cultivation

Jute thrives in warm, humid, and rainy environments, which is why the Ganges Delta of India and Bangladesh remains the world’s largest production zone. The plant requires:

-

Temperature: 24°C to 38°C

-

Rainfall: 150–200 cm per year

-

Soil: Loamy or alluvial soil rich in nutrients

-

Growing Period: 4 to 5 months from sowing to harvest

Farmers usually sow jute seeds during the pre-monsoon season (March–May). The plants grow rapidly and can reach up to 12 feet in height by the time of harvest. Minimal chemical fertilizer or pesticide is required, making jute one of the most low-input, high-yield crops in the world.

After 120–150 days, when the plants start flowering, they are harvested. The stems are cut close to the ground and bundled for the next critical stage — retting.

The Retting Process: Where Fiber Meets Nature

Retting is the traditional, eco-friendly process that separates jute fibers from the woody stalk. The bundles of harvested jute are immersed in slow-moving or stagnant water bodies (like ponds, rivers, or canals) for 10 to 25 days. During this period, microbial fermentation softens the plant tissues, loosening the fibers.

Once retting is complete, farmers extract the fibers by hand — a process called stripping. The fibers are then washed, dried under sunlight, and sorted according to color, fineness, and strength.

This natural retting method is what gives jute its smooth texture and soft feel. However, with growing concerns about water usage and runoff pollution, researchers are now developing enzyme-based retting methods to make the process faster and more environmentally controlled.

Grades and Quality of Jute Fiber

The quality of jute depends on several factors:

-

Variety of plant (Tossa or White jute)

-

Soil and climate conditions

-

Harvesting time

-

Retting duration

-

Extraction method

Fibers are graded based on color, strength, fineness, and luster — ranging from Grade 1 (superior) to Grade 8 (inferior).

-

Tossa jute usually commands a premium because of its golden color, strength, and smooth texture.

-

White jute is coarser and preferred for industrial sacks and heavy-duty fabric.

| Property | Jute | Cotton | Hemp | Flax |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water Usage | Low | Very high | Low | Moderate |

| Fertilizer Needs | Minimal | High | Minimal | Moderate |

| Tensile Strength | High | Moderate | Very high | High |

| Biodegradability | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Cultivation Period | 4–5 months | 6–7 months | 3–4 months | 3–4 months |

Jute’s low water requirement and natural pest resistance make it one of the most sustainable fibers on Earth. Moreover, it captures a large amount of carbon dioxide during its short growth cycle — up to 15 tons of CO₂ per hectare — and releases 11 tons of oxygen, effectively acting as a natural carbon sink.

Cultural and Economic Importance

Jute has deep cultural roots, particularly in Bengal, where it is woven into folklore, livelihoods, and daily life. From mats and ropes to decorative wall hangings, jute’s versatility has long been celebrated in rural craftsmanship.

Economically, jute has been a lifeline for millions of farmers and workers in South Asia. In India and Bangladesh alone, over 4 million farmers depend directly on jute cultivation, while hundreds of thousands of mill workers rely on the processing and export industries.

Jute exports have historically contributed a significant share of foreign exchange for these economies, rivaling tea and textiles during the mid-20th century.

Modern-Day Uses and Applications

While jute’s traditional use was largely limited to gunny sacks, ropes, and mats, the fiber has undergone a revolution in recent decades. With growing interest in eco-friendly materials, jute now finds application in diverse industries:

-

Textiles and Fashion: Designers use jute fabric for handbags, shoes, jackets, and accessories. Its rustic appeal blends well with contemporary eco-fashion.

-

Home Décor: Jute rugs, curtains, cushion covers, and furniture upholstery add natural elegance to interiors.

-

Industrial Uses: Jute geotextiles are used for soil erosion control, road construction, and landscaping.

-

Paper and Pulp Industry: Jute is processed into eco-friendly paper, stationery, and packaging.

-

Composites: Jute fiber-reinforced composites are increasingly used in automobile interiors, replacing non-recyclable synthetics.

-

Agriculture: Jute mats and nets are used for mulching, weed control, and plant protection.

These innovations have positioned jute not just as a traditional fiber but as a modern material for sustainable development.

Environmental Significance

The environmental credentials of jute are outstanding. Every part of the plant can be used:

-

Fibers become cloth and ropes.

-

Jute sticks are used as biofuel, charcoal, and construction material.

-

Leaves and roots enrich the soil.

Unlike synthetic fibers, jute production does not involve harmful chemicals. Its biodegradability ensures zero waste after use. In fact, when jute decomposes, it releases nutrients back into the soil, supporting a circular ecological cycle.

Additionally, jute crops enhance soil fertility and help prevent erosion — a vital benefit for flood-prone regions. Its cultivation improves the water-holding capacity of soil, creating favorable conditions for subsequent crops such as rice or maize.

Jute as a Sustainable Solution

The global call for sustainability has brought jute back to the spotlight. Countries around the world are banning single-use plastics, and consumers are increasingly demanding biodegradable alternatives. Jute answers both needs beautifully.

A single jute bag can last for years and replace hundreds of plastic ones, significantly reducing landfill and ocean waste. When disposed of, it breaks down naturally without releasing toxins.

Moreover, the energy consumption in jute manufacturing is much lower than synthetic materials. As governments and businesses set ambitious carbon reduction goals, jute stands out as a natural, scalable solution to pollution and waste.

Innovation and Research

Recent years have witnessed remarkable innovations in jute processing and product development:

-

Softening agents make jute fabric smoother for apparel.

-

Blended textiles (like jute-cotton and jute-silk) enhance comfort and style.

-

Biochemical retting techniques are reducing water pollution.

-

Nano-jute fibers are being researched for high-strength composites and filtration materials.

Institutions like the Indian Jute Industries’ Research Association (IJIRA) and Bangladesh Jute Research Institute (BJRI) are actively working to modernize production and diversify jute applications, ensuring its relevance in the 21st century.

Symbolism and Legacy

Beyond its physical properties, jute carries symbolic meaning — representing resilience, simplicity, and harmony with nature. It has survived colonial exploitation, industrial decline, and competition from plastics, yet continues to reinvent itself in the age of sustainability.

For many rural families, jute is more than a crop; it’s a heritage. For modern societies, it’s a lesson that nature can provide all we need if we cultivate it responsibly. And at Ap commercials best jute bags manufacturers in India, we make sure that we balance between both.